My Mr. PC: Paul Carr (Part I)

On Houston's Kashmere Stage Band, meeting Wynton & Branford Marsalis, Howard University and staying in D.C. over moving to NYC

I remember driving up to a nondescript suburban house on Middlevale Lane in northern Silver Spring, MD. Out front was a spacious down-sloping front yard, a large driveway big enough for at least six cars plus garage. As I approached the door, a white toy poodle greeted me eagerly jumping on the door with a steady and eager bark. I was probably 16 years-old. I think I had my YAS-62 in a clunky AKB case.

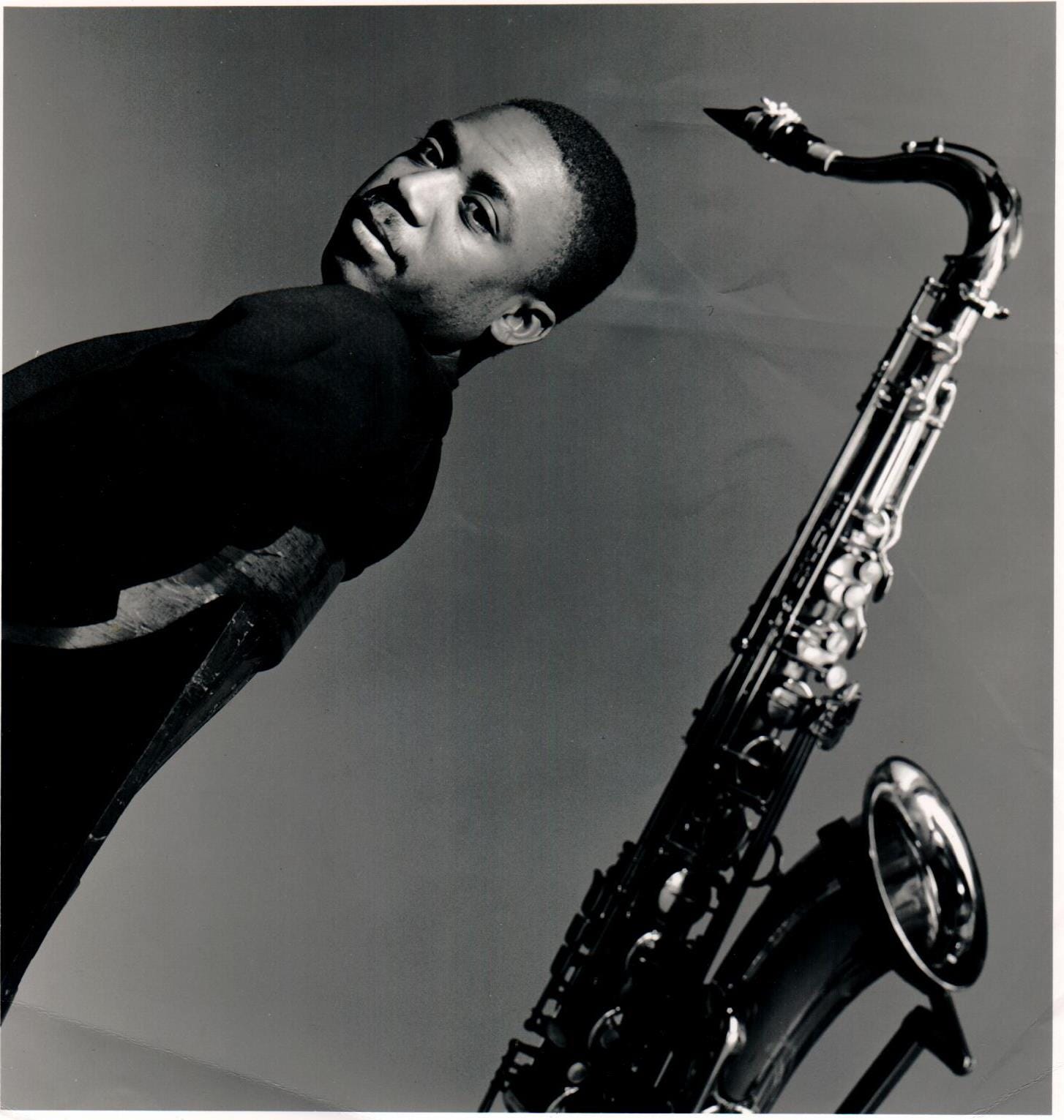

I had arrived to meet Paul Carr, who at the time was known the DC Metro area mainly as a journeyman tenor player whom you could see at Takoma Station, Blues Alley, Caton Castle, Twins Jazz and a host of other small venues. Among a smaller subset of young students, Carr was known as an ace saxophone teacher, who could give you the basics to move forward with a grounding in jazz language to achieve the goals you had for your playing.

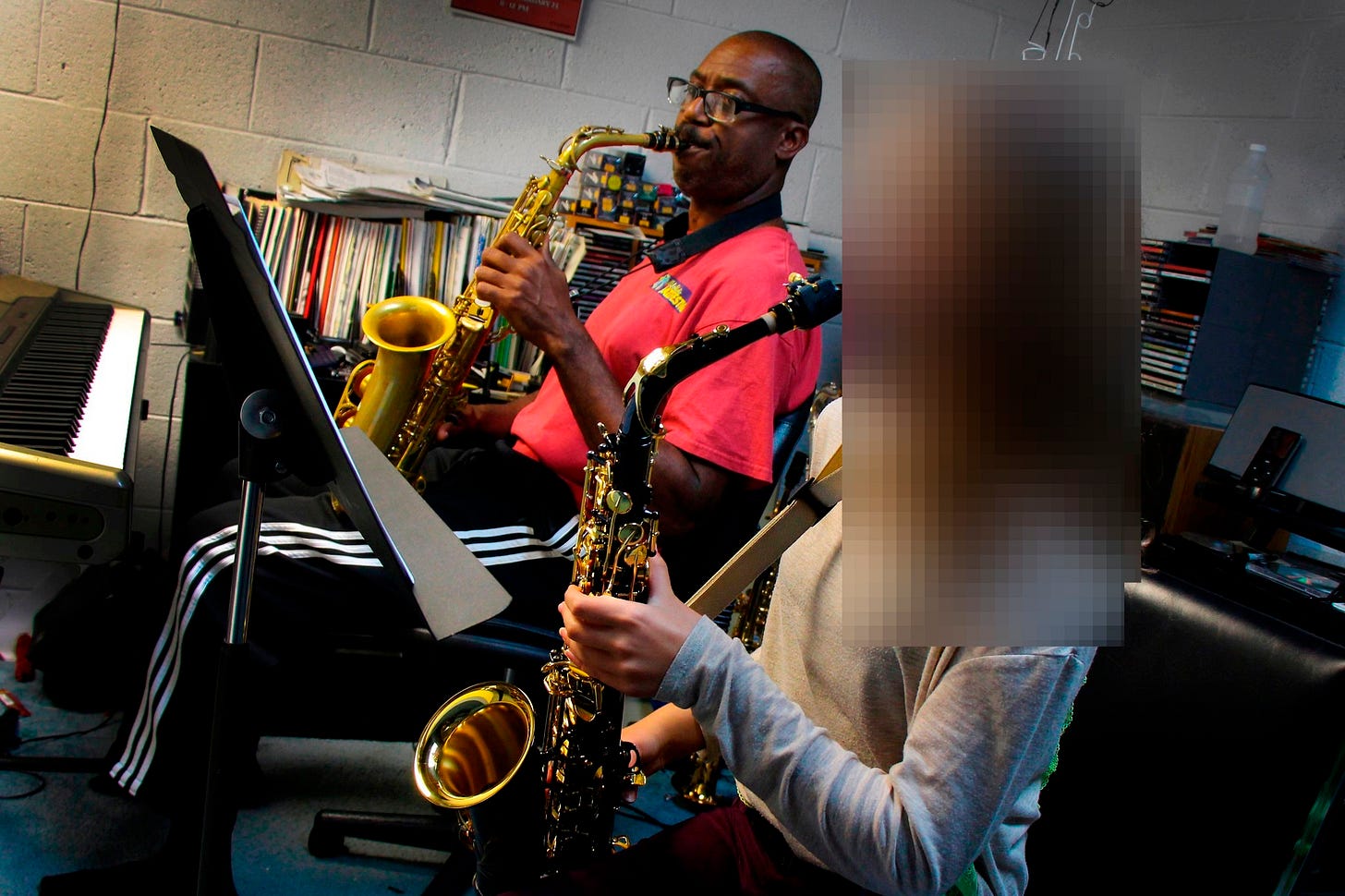

Paul taught out of his basement. A hodgepodge of saxophone and golfing gear was typically strewn about the place in addition to a personal computer at broad executive office desk. A treadmill, sat in one corner with some free weights and there was big-screen TV. As you turned right off the stairs and swung around in the opposite direction, you saw a cozy room crammed with a mini-keyboard, a full stereo (with turntable), tons of CDs, some old vinyl, two chairs, a few saxophones (usually at least a soprano, a tenor and an alto), and Jamey Aebersolds galore.

While my contemporaries were swept up in Britney Spears, Kid Rock, Christina Aguilera, Backstreet Boys and Linkin Park, I was listening to Ellington, Basie, Woody Herman, Ella, Bird, Miles, Trane and Herbie. Word-of-mouth had gotten me to this basement studio. This was a good six years before YouTube; easily a decade or more before Facebook or Instagram. You see, I had been frustrated for a minute. While I had excellent ears and could play decently over changes and read pretty well, I couldn’t make the leap to any of the local honors bands like All-County Jazz Band or All-State Jazz Ensemble. At the time, at least in the D.C. area, there wasn’t much in the way of extra-curricular jazz programs (I had briefly been in a student ensemble at the Levine School of Music led by Jeffrey Chappell).

After a bit of investigation, I found out about an alto player a year or two older than me named Paul Hazen, who was making it into these honors bands. Hazen recommended I check out Paul live. So one Saturday night not long after, I found myself at a concert at Dumbarton Church, billed as “Battle of the Saxes” (linked is a brief concert review by Mike Joyce in the Washington Post that ran the day after the show). That evening was a major aha moment in my young jazz life. The other players were Ron Holloway and the legendary D.C. tenorman known as “the Wailin’ Mailman,” Buck Hill. I quickly knew Paul would be a game-changer for me, after two or three decent teachers who were mostly members of DC’s military jazz ensembles.

By my senior year (Fall 2000), I made it into both All-County and All-State jazz bands as second alto. In these honors bands, I met many of the players who would become friends for years to come: Jacob Teichroew, Adam Kinner, Jason Marshall and more. All of us had Paul Carr in common as our mentor.

As a saxophonist, educator, mentor, administrator, camp director, and festival director, Paul has meant so much to myself and so many fellow musicians and jazz fans, both in the DC area and beyond through his tireless work as a teacher and jazz advocate. In 2002, shortly after I left for college, he founded the Jazz Academy of Music, which hosts summer camps and jazz ensembles for kids throughout the school year. His students have gone on to attend Howard University, Juilliard, Manhattan School of Music and Berklee College of Music. Paul also mentored trumpeter Terell Stafford and alto saxophonist Bruce Williams. He served as Professor and Jazz Band Director at Gettysburg College until 2021. He remains an active guest conductor and clinician at high school jazz and collegiate festivals. He is currently writing a book to codify his teaching techniques, The Theoryless Approach to Jazz Improvisation.

The last time I interviewed Paul was in 2004. So I thought it was time for an update. Some know him on social media over the past decade for the hashtag, #realjazz2, and from the festival’s old slogan “standing up for real jazz.” Carr was always an advocate for the classic jazz sound, as formulated by African-American players in the 1940s-1970s, but at the time, and even today, as reflected by his programming of the Mid Atlantic Jazz Festival, which welcomes a host of styles, Paul is anything but a staunch traditionalist.

In 2010, Paul re-established the former East Coast Jazz Festival, which I had attended as a youth, and renamed it the Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival. He serves as its Executive and Artistic Director, along with much help from his wife, Karmen Carr, the head of her own consulting firm. Since then they have hosted the likes of NEA Jazz Masters Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, Ellis Marsalis, Roy Haynes, Branford Marsalis, Dr. Lonnie Smith and Delfeayo Marsalis as well as Gregory Porter, Buster Williams, Rufus Reid, Kurt Elling, Orrin Evans, Nicholas Payton, Chris Potter, Regina Carter, Freddy Cole, Joey DeFrancesco, Carmen Lundy, Vincent Herring, Terri Lyne Carrington, Allison Miller, Gary Bartz, Jazzmeia Horn, James Carter, René Marie, Camille Thurman, The Baylor Project, Sharel Cassity, and many more.

Some of the 2025 highlights include säje, Tia Fuller, Orrin Evans with Chris Potter, Jeff ‘Tain’ Watts and Dwayne Dolphin, Geoff Keezer & Gillian Margot, Cyrus Chestnut featuring Ekep Nkwelle and many others. Check out the full lineup for this year’s festival taking place February 14-16, 2025 at the Bethesda Marriott on Pooks Hill Rd.

If I had to think of a true jazz hero, stretching from deep influence in education, to being one of the strongest performers to concert/festival presentation, I can’t think of many folks as impactful as Paul has been. Here is Part I of my conversation with Paul Carr.

Paul Carr (PC): My name is Paul Carr. I’m a saxophonist, an educator, and a jazz presenter. I produce the Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival, and now I’m producing a couple of jazz series as well. I also conduct a youth orchestra.

Matt Merewitz (MM): Great. Tell me about your beginnings in music. Who was your first music teacher? How did you start playing saxophone? What music did your parents listen to?

PC: I grew up in Houston, Texas. My mother was a jazz fan, so I was introduced to jazz early on because she played it all the time. She told me that once I was big enough, she would get me a saxophone. She even bought me toy saxophones when I was young.

The first time I had the opportunity to play was in elementary school, around 5th or 6th grade. Our junior high school was right across the way, and the band director, Warren E. Turner, came over to show us the instruments. He tried to steer me toward the trumpet, but I told him, “My mom said I’m going to play the saxophone.” He was a saxophonist himself, so that worked out well. He went to North Texas and was in the same class as Billy Harper. He used to tell me all the time how much Billy Harper practiced.

MM: When you say your mom was a jazz fan, who were her favorites?

PC: Her taste was eclectic. She listened to blues—B.B. King, Les McCann, Eddie Harris. She loved CTI, Grover Washington Jr. and Stanley Turrentine. Cannonball Adderley was a favorite too.

It was mostly what would be described today as soul jazz. She also had records by Johnny Hammond and Hank Crawford. It wasn’t the really old-school jazz; it was music from the late ’60s and early ’70s.

One defining moment for me was hearing Grover Washington Jr. play “It’s Impossible.” He burned through those changes, and I remember thinking, That’s the sound I want.

MM: Do you remember the first time you saw a live musician or attended a concert?

PC: It was probably on that same path somewhere. The big star in Houston at the time was Arnett Cobb.

MM: Right, he was on Prestige and Muse at different points.

PC: Yes, exactly. The first time I saw a concert, someone took me to see Arnett Cobb play at a club called Le Bastille. I saw so many legends there—Hank Crawford, Freddie Hubbard, Arnett Cobb, and Don Wilkerson, another great tenor player from Houston. Those were some of my earliest live music experiences.

MM: You and I have a special relationship because you were my teacher when I was 16 and on. I remember seeing you perform at Dumbarton Church with Buck Hill and Ron Holloway. That was a major catalyst for me—I realized I needed to get serious about studying jazz, and I wanted to learn from you. Did you have a similar moment in your childhood where you realized, This is the person who’s going to take me to the next level as a musician?

PC: It was all laid out for me. I was in junior high school and had options—I could have gone to the High School for the Performing & Visual Arts or Kashmere High School. Kashmere had the renowned Kashmere Stage Band, which had a huge reputation long before I got there.

All my older sisters went to Kashmere. I’m the fifth in a line of six kids, and the Kashmere Stage Band was world-famous. In the late ’60s, they toured and played at festivals where they were the only African American band competing in the South and often winning. A few times they got stiffed, but they were so good it was obvious they deserved to win.

The conductor, Conrad “Prof” Johnson, was a saxophonist who knew everyone. He was great friends with Arnett Cobb, Don Wilkerson, and other musicians coming through town. Grover Washington Jr. even visited the school. Prof was instrumental in everything. He recorded an album with the band every year. One of my sisters brought home a Kashmere Stage Band record, and that was it—I knew I wanted to be in that band.

[Editor’s Note: Jamie Foxx co-produced a documentary film about Kashmere Stage Band and Conrad Johnson called Thunder Soul, released in 2010.]

My junior high school band director, Mr. Turner, tried to get me to consider HSPVA. I remember him saying, “Son, HSPVA is in the cafeteria. You should go over there and talk to them.” I told him, “I’m going to Kashmere. I want to play in the Kashmere Stage Band.” He looked at me and said, “And then what, son?”

He wanted me to be a well-rounded musician. Many students who played in the Kashmere Stage Band didn’t pursue music beyond high school. Since it was a public school, some just played for the experience and then moved on. Mr. Turner wanted me to go somewhere that could give me a better chance at a long-term career, but I was set on Kashmere.

Prof wrote and arranged the tunes to highlight the band’s strengths. Since he was a saxophonist, the saxophones had the moving parts while the brass delivered punch lines. By the time I got there, all the moves were already in place. The tunes had been recorded, so we knew the choreography—standing up, moving side to side, the trumpets going up—it was all part of the show.

During my senior year, I had more opportunities to play because there had been a senior ahead of me the previous year. That year, every festival we entered, we won, and I was recognized as a soloist.

MM: During that time, were you seeing major artists like Sly Stone or Earth Wind & Fire come through Houston, or were you really focused on jazz?

PC: I was really focused on jazz. My older sisters were into Sly Stone, the O’Jays, and the Temptations, so I heard all of that at home during parties and gatherings. But once I got into jazz, I stuck with it. I did love Earth, Wind & Fire because of their horn section. The tunes were so good. I played in a band that covered them, and I even learned Don Myrick’s solo on “Reasons,” and played it at a talent show once. EWF was huge, and we played their songs in the marching band too.

I also got into Tower of Power. I remember buying Live and in Living Color and bringing it to Prof. I played him Lenny Pickett’s solo, with all the circular breathing and crazy technique. He listened, shook his head, took the record off, and put on a Charlie Parker album, saying, “Now listen to this.”

MM: Ha! Now you started out at a junior college in Texas before transferring to Howard, right?

PC: No, I went to Texas Southern, an HBCU in the Southwestern Athletic Conference. We played Jackson State, Grambling, all those schools. The band director, Lanny Steele, was a pianist who had played with Cannonball Adderley and Arnett Cobb others. He loved creative music and wrote challenging charts—hard to read, but unique. If we got in the ballpark with them, the band would sound different from everyone else.

My freshman year at Texas Southern, I sat next to Kirk Whalum, who was a couple of years older than me. We went to the Notre Dame Jazz Festival that year. Kirk won a soloist award. The judges said our band was so unique they couldn’t even rate us.

MM: Oh, really? Because you were playing these unique compositions?

PC: Absolutely.

MM: And you were the only African-American band there?

PC: Yeah, we were the only Black band there. A lot of the other bands sounded like Woody Herman, but we really appreciated their musicianship. Even though they had a similar sound, the level of playing was extremely high. I knew we had good players, but we needed to step it up a bit.

MM: Let’s talk a bit about the de facto white “ownership” of jazz as an business or in the collegiate sphere? You go to Notre Dame Jazz Festival, which is run by white people, but you come from a predominantly Black high school and HBCU. Was there any culture shock? Did you realize that jazz was being approached in a completely different way?

PC: We realized it, but we didn’t talk about it directly. It was just the way things were. Growing up in Texas, you were conditioned to see white people in charge. You were also taught how to behave in certain situations. My dad once got pulled over, and I noticed his whole demeanor changed—he spoke more politely and was extra cooperative. Afterward, he told me, “That’s how you have to act when you get stopped by the police.” I wasn’t even driving yet, but that lesson stuck with me.

So no, we didn’t dwell on it at the time. I didn’t really think about it until I got older and started producing jazz concerts. That’s when I noticed how few African Americans were in charge of presenting this music.

MM: When do you think that shift happened? The ’50s? ’60s? ’70s? Did it change when Black popular music moved away from jazz and into other genres?

PC: Maybe the ’70s. That was kind of a dry period for jazz. Fusion was taking off, and traditional jazz wasn’t as dominant. Even today, in Maryland, there are very few Black-owned jazz venues. One of the few is Caton Castle, and he’s been doing it for years. Westminster Church has a jazz series, but it’s curated by a white pastor.

MM: Right, so the people presenting jazz today are mostly white?

PC: Exactly. But here’s the thing—most people who present jazz, love it. If you have money to invest, there are a lot of other, more profitable businesses you could go into. Jazz isn’t an easy way to make money. That’s why I respect anyone who presents jazz, because they don’t have to do it.

MM: They’re operating at a loss.

PC: Most of the time, yeah. That’s why I always make sure to thank presenters. They’re doing it out of love for the music.

MM: Going back a bit, you eventually transferred to Howard University. Tell me about that experience. Who was there with you?

PC: I got to Howard in 1983. I first heard about Howard through their jazz ensemble records. I listened to one and thought, “That’s where I want to be.” On that record were Roger Woods, Gary Thomas, and Clarence Seay on bass. My future wife and I came up to visit her brother, and she went on a job interview just for fun. She got the job, and next thing you know, I transferred to Howard, and we moved to D.C. When I got into the band, Chris Royal was there on trumpet. His brother, Gregory Royal, later bought JazzTimes. Also, Meshell Ndegeocello’s brother was in the band—he played guitar.

MM: You told me Tim Warfield was there too, right?

PC: That’s right. Tim came to Howard about a year after I did. He was actually an architecture major. One day, I heard him practicing in a practice room, so I opened the door and said, “Who are you?”

MM: Uh-huh.

PC: He was never officially in the band. At the time, Howard had two bands—an A band and a B band—and I don’t think he was even in the B band. But he started hanging out with us all the time, just like he was part of the music department. We played in a little band together, so I saw him every day. I’m not sure if he ever switched to being a music major, but he stayed in architecture.

MM: That actually makes sense. The way he dresses, his glasses—he looks like an architect.

PC: Exactly. He’s very particular, very intentional.

MM: So, you graduate from Howard in 1985 and decide to stay in D.C. instead of moving to New York, like a lot of your peers. Between that time and when I met you in ‘99, were you just gigging and teaching around the D.C.-Maryland area?

PC: Yeah. If you met me in 1999, that was probably right when I moved to Middleville Lane. I think we moved there that year. When I finished at Howard, I was playing in a Haitian band, and we used to go up to New York every weekend. We played on double bills, always as the headliner. We’d leave D.C. at 6:00 PM on a Friday, get stuck in traffic, and finally make it to New York around 11 PM or 12 AM. It didn’t really matter because the other bands always played first. That band was a regular gig for a while.

After that, I started playing at Takoma Station as a sideman with trumpeter Cameron Brown. A year or two later, I ended up leading the band there. I was always playing. I thought about moving to New York—I even looked into apartments with Michael Bowie and a couple of other guys—but I never pursued it seriously.

MM: Why not?

PC: I was older when I got to Howard—about 22 or 23—and had just gotten married. My wife was climbing the corporate ladder, and I was already working regularly in D.C. Then my gig at Takoma Station expanded to three nights a week. I’d go down to One Step Down and hear these incredible players. I’d ask them what they had after their gig, and many would say, “Nothing.” They were coming down from New York just for that one show. That made me think twice about leaving.

MM: Who were some of the musicians you saw at One Step Down?

PC: Everybody—Freddie Hubbard, Joe Henderson. I talked to Joe for a long time at the bar. Vincent Herring, Seamus Blake, Russell Malone, Don Byron, Don Pullen.

MM: Don Pullen, yeah!

PC: Yeah, he was great. And Ann, who ran One Step Down, really loved piano players. She might have been a pianist herself because she always made sure the piano was in top shape. She hired the best pianists. I remember seeing one of Cyrus Chestnut’s first gigs with Freddie Hubbard.

MM: Would the Jazz Messengers play there, or was it too small for them?

PC: Too small. It was right on Pennsylvania Avenue, very intimate. I actually saw the Messengers for the first time in Houston in 1980. That was the band with Wynton—back when he had the afro—Billy Pierce, Bobby Watson, James Williams.

MM: So in 1980, you’re about 20 years old, and you see that band. It must have been a mind-blowing experience.

PC: Completely. I came back and told Sheldon “Fig” Newton, a percussionist who played with Ahmad Jamal, all about it. He just said, “Man, I saw them in Brussels, and he said, you know what? He has a brother who plays saxophone. I said, really? Can he play? And he said, yeah, and you know what else he said? You would like him. I’ve told Branford that story a hundred times. When I met Branford, it was just like that. Within five minutes, we were out the door, and we hung out the whole day, the first time I met him. That was in the early ‘80s, maybe around ‘82, during Wynton’s first tour. Wynton was doing a masterclass at the University of Houston, but for some reason, it never materialized. So, I walked up to him, and I said, “I play saxophone, and I’d really like to meet your brother.” He said, “Okay, cool. You got a car?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Well, take me to McDonald’s.”

MM: Uh-huh.

PC: We’re at McDonald’s, and Wynton starts humming solos out loud. He goes, “Do you know that solo?” He was just humming them in the middle of McDonald’s. Afterward, he took me to the hotel, opened the door and there was Branford sitting in bed, watching cartoons. Wynton said, “This guy wants to meet you.” Branford said, “Come on in.” We sat down, talked, and he asked, “Do you play saxophone?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “I want to hear you play.” I said, “No need.” But he insisted. So, I grabbed my horn, started playing, and once I got into it, he said, “That’s enough. Where are we hanging out today?” He was serious. We had lunch, I took him to the college, and we just had a great day. That’s how we met, and we’re still like that today.

MM: This brings up a bigger question I’ve been thinking about for this series: Who are the people who aren’t household names who made big things happen for others, changed lives in their own special way? For me, you were one of those people. You really lit the Cannonball Adderley fire, the Arnett Cobb fire, the Kenny Garrett fire. You played me Songbook the first time we got together. That album was my bible for years. You told me about Roy Hargrove. You were a major catalyst for me. When did you first experience the joy of teaching? When did you catch that?

PC: It was at Texas Southern. My saxophone teacher, Laura Hunter, had just come from the University of Michigan. She was a student of Don Sinta. She was in her mid-20s, a white female coming to Texas to teach, and it was a culture shock for her. She couldn’t understand why people weren’t practicing. She came from Michigan, and she told me, “You need to learn something.” But I didn’t do it, so she kicked me out of her studio and said, “Don’t come back until you can play this.” She was upset, but it made me practice.

She also told me other things about myself that faculty members had mentioned—how I was backsliding, just getting by. I started practicing and diving into saxophone literature, especially classical, which I love. Laura taught me all of that, and she was teaching some kids in Spring, Texas, about 40 miles up the road. She asked me to teach them when she was out of town. When she came back, she asked, “How did the teaching go?” I said I liked it. She said, “Well, they liked you more than they liked me. Can you finish out the rest of the year?” That’s how I got into teaching. It felt like an extension of playing—I had my horn in my hand and had to figure out how to explain things differently, which helped me understand what I was trying to do.

MM: You’ve taught some amazing students—Braxton Cook, Jason Marshall, Adam Kinner, Pete and Will Reardon-Anderson, Tyrone Allen, Alex Hoffman, Tommy Gardner, Aaron Seeber, Dan Pappalardo, Bruce Williams. Can you name any others?

PC: Yeah, I’ve taught Ben Wolstein, who’s playing bass now. Alex Hamburger. The Andrew and Chris Latona are doing very well in New York. There are more, I’m sure, but those are the ones I can remember right now.

Part II of this interview is now live. Paul Carr speaks on how Black audiences are overlooked in jazz programming; his quest to “stand up for real jazz"; the fallacy of treating jazz like pop music; and women (particularly his wife, Karmen) in jazz organizing.

This is great. I studied jazz with Paul about 1995, but I'm a trombone player! My dad and Karmen worked together at the time. This was before they moved to Silver Spring. A different basement but probably the same poodle. :)

A true saint for what he does for the music, mentorship and education…PC is effortlessly hip, has one of the smoothest golf swings in Jazz, and is a friend to all. Thank you for giving him his due Matt!